(2021)

Text - Design Research - (Self-) Publishing

(De-)Ornament - Fragmented Passages of Gender & Ornament

“Clothing is one of the most immediate and effective examples of the way in which bodies are gendered, made ‘feminine’ or ‘masculine’.”1

When it comes to garments, it becomes quite clear how gender is everywhere. As a society we are focused on segregating clothing into binary-gendered boxes: choices that are made seemingly unconsciously. It is clear for almost every garment if it is meant to be worn by either men or women. This differentiation is made visual in the way our garments are decorated and ornamented. These decorations can be seen as signals that refer to a specific binary gender. However, these signals form the case of codes and constructs that remain invisible for most people, because we have been trained to look over them. The goal of (De-)Ornament is to unravel a visual culture consisting of these labels, signals and codes related to the gender binary and make them readable and visible.

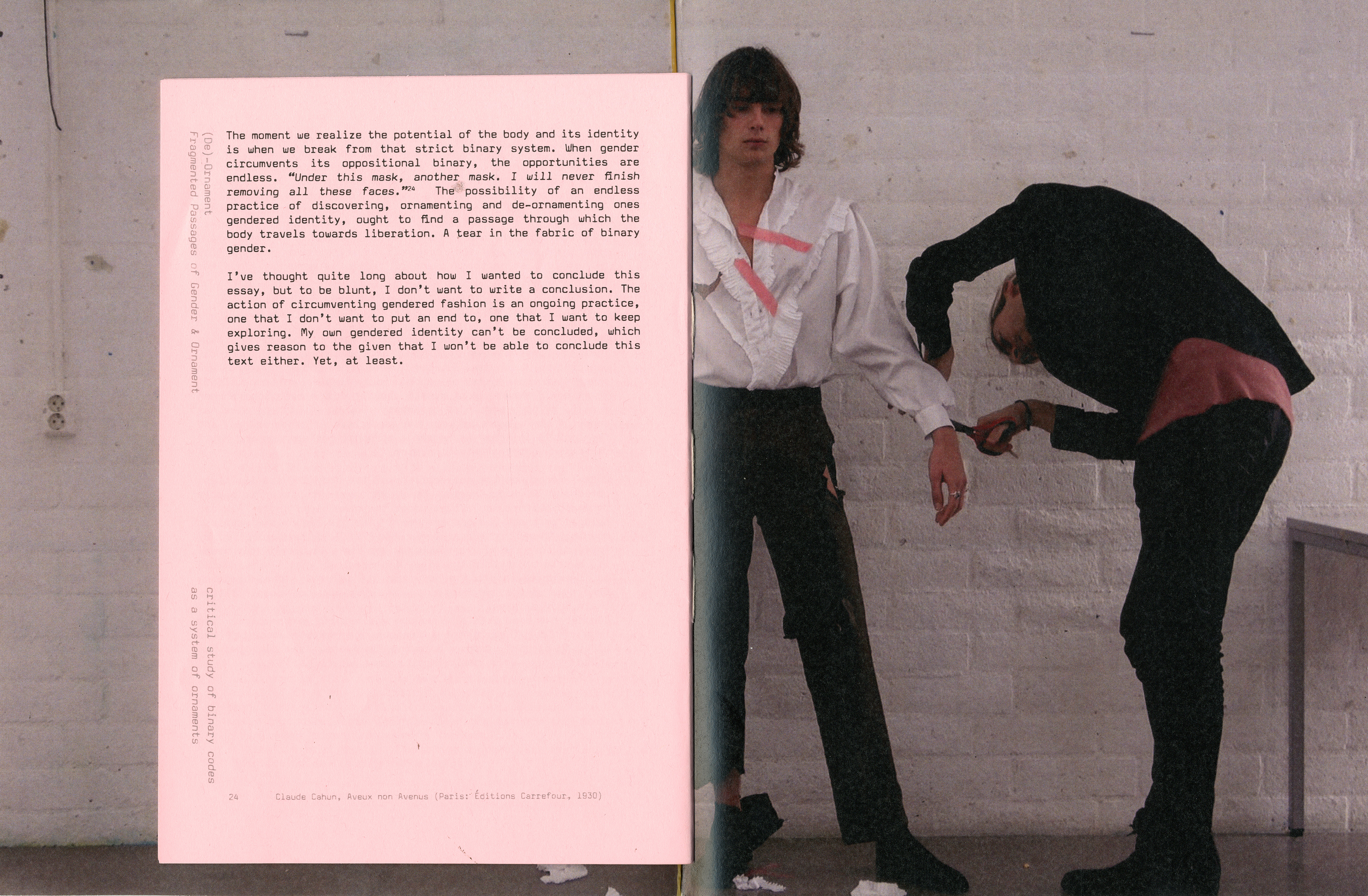

I use my Male to Female Dress practice, a research method I established 2019. Through experimenting with placing my own body and consciousness in processes of ornamenting and de-ornamenting garments, I try to create understanding and meaning in the way garments are gendered through ornamentation. These awareness practices aim to circumvent our existing relationship with gendered fashion, starting with personal conversations about gender, fashion and the discoursed struggle that stands between the two.

By using this method of research I liberate the process from the product. The resulting garments don’t carry all of meaning I try to convey within my work. Thus, I decided that that the process — performative embodied research processes — can take the shape of a product. The process is a presence within my work that creates and forms meaning. This publication aims to function as an aid to take you (the spectator) by the hand and guide you through my performative work.

- Besides the previously explained aim of my work, this publication should also function as an explanatory guide for reproductive practices of the discoursed performative work. As the outcomes and explanations of the performances are strongly related to personal views, matters and contexts, by reenacting one could explore one’s own opinion and view on the matters discussed. -

- This publication also includes a mini-zine consisting of additional textual works in the form of an essay that describes the relationship between gender and ornamentation more profoundly. -

- This publication also includes a mini-zine consisting of additional textual works in the form of an essay that describes the relationship between gender and ornamentation more profoundly. -

- Joanne Entwistle, The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress & Modern Sociaal Theory, Second Edition (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015)

An introduction to

(De-)Ornament;

Critical study of binary codes as a system of ornaments

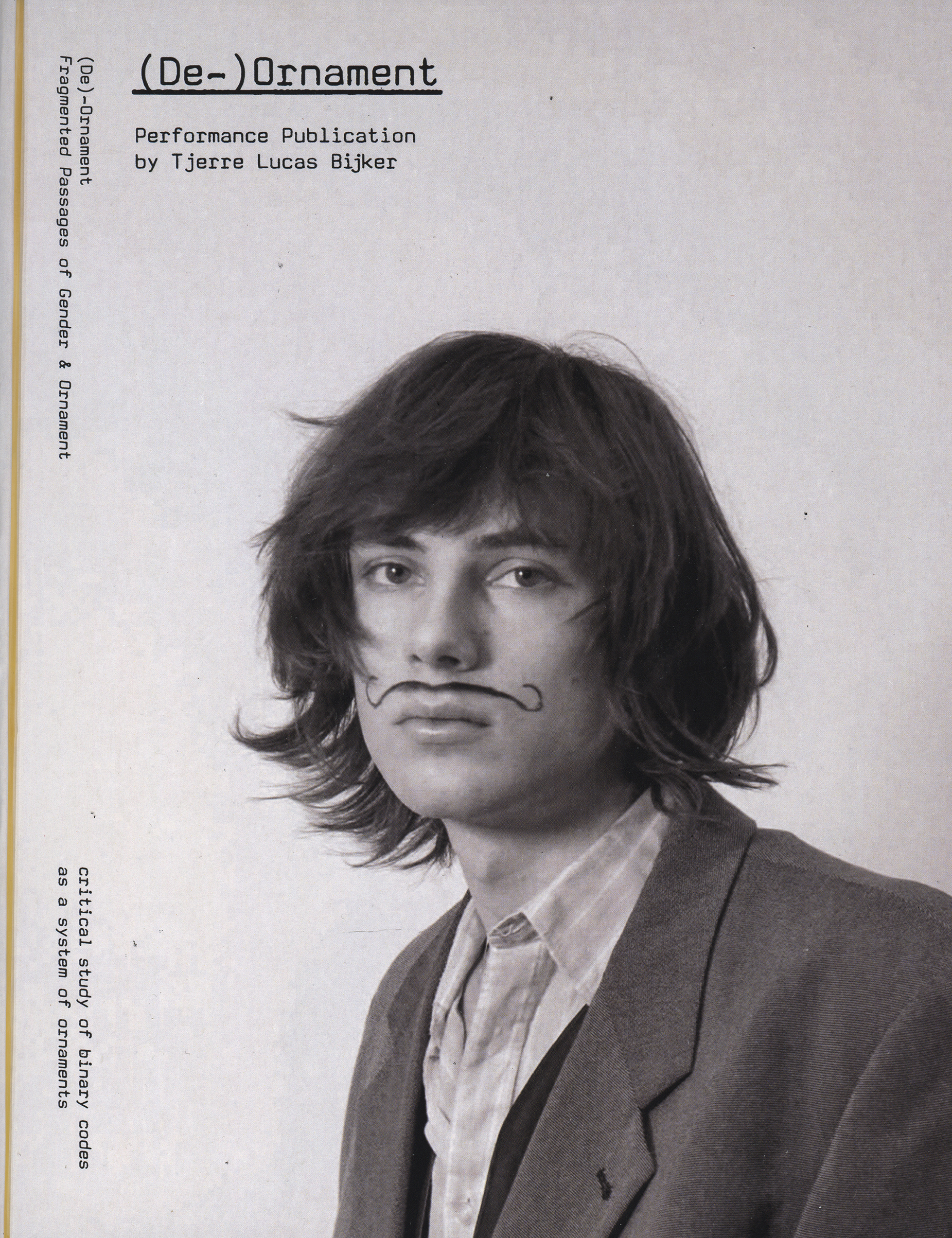

Since I was a young boy, I’ve always felt attracted to decorated garments: t-shirts with glittery prints and highly ornamental motives. I have vivid memories of trying on my sister’s and mother’s clothing and feeling absolutely beautiful. The way their garments flowed, sparkled and had beautiful floral prints made me so jealous. I had never seen such pieces that were made for me. Every time my mother and I went shopping in the ‘boys’ sections of malls and shops I was disappointed by the lack of ornamented garments. If there were any ornaments on the garments, they were often intensely non-descript using toned down colors and plain motives. And if there even was a print, it was always of typical boy stuff, cars for example. I, on the contrary, wanted to be colorful, bright and flamboyant. But that isn’t for boys is it? Let alone, for men?

“Clothing is one of the most immediate and effective examples of the way in which bodies are gendered, made ‘feminine’ or ‘masculine’.”1

Legacy Russel, author of ‘Glitch Feminism’, states how “Gender is, to call on a term coined by philosopher Timothy Morton, a hyperobject. It is all-encompassing, it out-scales us. As such, it becomes difficult to see the edges of gender when submerged within logic, thereby bolstering the fantasy of its permanence through its apparent omnipresence. In short, gender is so big, it becomes invisible.”2

When it comes to garments, it becomes quite clear how gender is indeed everywhere. As a society we are focused on segregating clothing into binary-gendered boxes: choices that are made seemingly unconsciously. It is clear for almost every garment if it is meant to be worn by either men or women. For example, how the garments are closed gives instruction about whom should be wearing it. The shirt could be exactly the same, but because it closes right over left it should be worn be a woman. There are a few exceptions to the rule: pieces such as t-shirts and sweatshirts come to mind. These pieces are seemingly so basic, that it doesn’t matter who wears them. In order for these pieces to “fit” inside a certain gender category however, they are often very heavily decorated, or heavily not-decorated for that matter. As stated before, children’s t-shirts have the same construction and fit, but are decorated in a way that dictates if it should be worn by either a boy or a girl. When I was young, I could have searched high and low for a ‘boys’ t-shirts with glittery prints and highly ornamental motives, but I probably would have never found one.

These decorations can be seen as signals that refer to a specific binary gender. These signals form a wide range of codes and constructs that remain invisible to most people, because we have been unconsciously trained to look over them. In this textual and visual essay, my goal is to unravel these labels, signals and codes related to the gender binary and make them readable and visible.

- Joanne Entwistle, The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress & Modern Social Theory, Second Edition (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015)

- Legacy Russel, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (London: Verso, 2020).